A new scale for atmospheric rivers

Atmospheric rivers aren’t new. But they’re entering the public consciousness now, as they become more intense and frequent with global warming. A pair of atmospheric rivers are striking California now, for example, causing widespread flooding that’s expected to continue through Tuesday, March 14, 2023. Meanwhile, the American Geophysical Union (AGU) has released word of a new study that demonstrates the value of a recently developed intensity scale for atmospheric rivers.

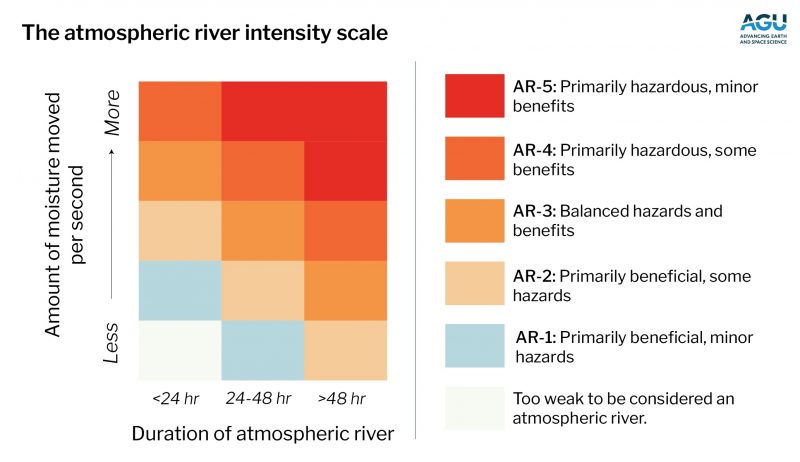

It’s much like the Saffir–Simpson scale that slots hurricanes into five categories: 1 (weakest) to 5 (strongest). The hurricane scale is based on sustained winds. The new atmospheric river scale also has five categories: AR-1 (weakest) to AR-5 (strongest).

It’s based on how long the atmospheric river lasts, and how much moisture it transports.

Last chance to get a moon phase calendar! Only a few left. On sale now.

Unending rain and dangerous flooding

The AGU’s peer-reviewed Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres published the new study earlier this year (January 2023). The scientists’ statement explained:

In part because some West Coast weather outlets are using the intensity scale, ‘atmospheric river’ is no longer an obscure meteorological term. Instead, it brings sharply to mind unending rain and dangerous flooding …

The string of atmospheric rivers that hit California in December and January, for instance, at times reached AR-4. Earlier in 2022, the atmospheric river that contributed to disastrous flooding in Pakistan was an AR-5, the most damaging, most intense atmospheric river rating.

The scale helps communities know whether an atmospheric river will bring benefit or cause chaos. The storms can deliver much-needed rain or snow. But if they’re too intense, they can cause flooding, landslides and power outages, as California and Pakistan experienced.

The most severe atmospheric rivers can cause hundreds of millions of dollars of damage in days in the western U.S.; damage in other regions has yet to be comprehensively assessed.

Striving for situational awareness

F. Martin Ralph is an atmospheric scientist at Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego and a co-author on the new study. He said:

Atmospheric rivers are the hurricanes of the West Coast when it comes to the public’s situational awareness. People need to know when they’re coming, have a sense for how extreme the storm will be, and know how to prepare.

This scale is designed to help answer all those questions.

Ralph and his colleagues originally developed the scale for the U.S. West Coast. They said their new study demonstrates that atmospheric river events can be directly compared globally using the intensity scale.

How they did the study

The researchers used climate data and their previously developed algorithm for identifying and tracking atmospheric rivers to build a database of intensity-ranked atmospheric river events around the globe over 40 years (1979/1980 to 2019/2020). Atmospheric scientist Bin Guan, who is affiliated with NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, led the study. He commented:

This study is a first step toward making the atmospheric river scale a globally useful tool for meteorologists and city planners. By mapping out the footprints of each atmospheric river rank globally, we can start to better understand the societal impacts of these events in many different regions.

More study results

The authors also found that more intense atmospheric rivers (AR-4 and AR-5) are less common than weaker events. And that AR-5 events occur only once every two to three years when globally averaged.

The most intense atmospheric rivers are also less likely to make landfall, and when they do, they are unlikely to maintain their strength for long and penetrate farther inland. Guan said:

They tend to dissipate soon after landfall, leaving their impacts most felt in coastal areas.

The study found four “centers,” or hotspots, of where AR-5s tend to die, in the extratropical North Pacific and Atlantic, Southeast Pacific, and Southeast Atlantic. Cities on the coasts within these hotspots, such as San Francisco and Lisbon, are most likely to see intense AR-5s make landfall.

Midlatitudes in general are the most likely regions to have atmospheric rivers of any rank.

Strong El Niño years are more likely to have more atmospheric rivers, and stronger ones at that, which is noteworthy because NOAA recently forecasted that an El Niño condition is likely to develop by the end of the summer this year.

Will TV meteorologists adopt the scale for atmospheric rivers?

While local meteorologists, news outlets and other West Coasters may have incorporated “atmospheric river” and the intensity scale into their lives, adoption has been slower elsewhere, Ralph said.

He hopes to see, within five years or so, meteorologists on TV around the world incorporating the atmospheric river intensity scale into their forecasts, telling people whether the atmospheric river will be beneficial or if they need to prepare for a serious storm.

Bottom line: Scientists are pushing an intensity scale for atmospheric rivers, much like the hurricane intensity scale. They think it’ll help keep people safer.