What is a day? You might casually talk about a day as a period of daylight. Or you could measure a day in relationship to the sun or the stars. Astronomers use the term solar day to describe a day relative to the sun. A solar day is the time from one solar noon – one local noon or high noon – to the next. It’s the interval between successive days as marked by the sun’s highest point in our sky. If you look at a day in that way, you can say that the longest days of the year come each year around the December solstice … no matter where you live on the globe.

The longest days are in December

What? Isn’t the shortest day for the Northern Hemisphere at the December solstice? Yes, it is, if we are talking about the period of daylight.

But, we’re talking about the (approximately) 24-hour interval from one solar noon to the next. In December, a day – one rotation of Earth relative to the noonday sun – is about half a minute longer than the average 24 hours, for the entire globe.

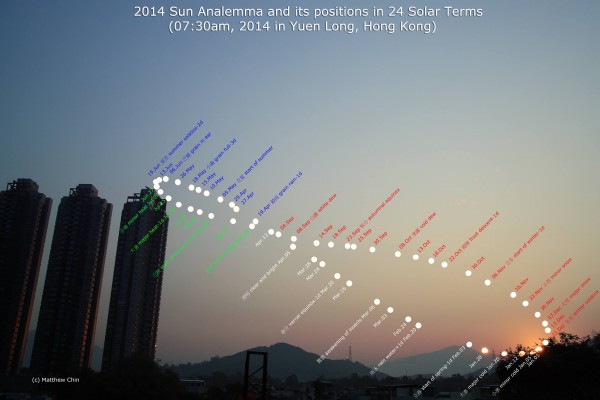

Keep in mind that the clocks on our walls don’t measure the true length of a day, as measured from solar noon to solar noon. To measure that sort of day, you’d need a sundial. A sundial will tell you the precise moment of local solar noon, when the sun reaches its highest point in the sky each day.

Days are always longer – as measured from one solar noon to the next – than 24 hours around the solstices, and less than 24 hours around the equinoxes.

Why are the days longer in December?

The days are at their longest now – for the entire globe – because we’re closer to the sun on the December solstice than we are at the June solstice. Earth’s perihelion – closest point to the sun – always comes in early January. So when we’re closest to the sun, our planet is moving a little faster than average in its orbit. That means our planet is traveling through space a little farther than average each day.

The result is that Earth has to rotate a little more on its axis for the sun to return to its noontime position. That effect lengthens the solar day by about eight seconds. In contrast, at aphelion, when the Earth is moving slower in its orbit, the solar day is about seven seconds shorter.

There’s another effect that happens during both the winter and summer solstices that increases the solar day by 21 seconds. It’s due to the way the sun moves mostly eastward, in relation to the stars, during solstices. Therefore, when the sun rises and moves up in the sky, it takes a bit longer to reach high noon from the previous day’s high noon.

For the winter solstice, the combined effects of these two phenomena increase the solar day by about 29 seconds.

Half a minute longer doesn’t sound like much, but the difference adds up. For instance, two weeks before the December solstice, noontime comes about seven minutes earlier by the clock than on the December solstice. And then two weeks after the December solstice, noon comes about seven minutes later by the clock than on the December solstice itself.

Sunrises and sunsets

Because the clock and sun are most out of sync right now, some befuddling phenomena cause people to scratch their heads at this time of the year. In the Northern Hemisphere, the year’s earliest sunsets precede the December winter solstice. And the year’s latest sunrises come after the December winter solstice. So the earliest sunsets came earlier in December for most of us; and the latest sunrises won’t come until early January.

In the Southern Hemisphere, the year’s earliest sunrises precede the December summer solstice, and the year’s latest sunsets come after the December summer solstice.

The fact that we’re closest to the sun in early January also means that Northern Hemisphere winter (Southern Hemisphere summer) is the shortest of the four seasons. Read more about the shortest season here.

However, at the same time … It’s the season of bountifully long solar days.

Visit Sunrise Sunset Calendars to find out the clock time for solar noon at your locality; remember to check the Solar noon box.

Bottom line: As measured from one solar noon to the next, December has the longest days – the longest interval from the sun’s highest point on one day to its highest point on the next day – for the entire Earth.